Article by By Melissa Korn – WSJ

With so many applying, fewer schools have one person read a whole application; plowing through 500 files in a day

As application numbers surge, admissions officers at some elite colleges say they don’t have time to read an entire file.

Instead, staffers from more schools—including the Georgia Institute of Technology, Rice University and Bucknell University in Pennsylvania—now divvy up individual applications. One person might review transcripts, test scores and counselor recommendations, while the other handles extracurricular activities and essays.

They read through their portions simultaneously, discuss their impressions about a candidate’s qualifications, flag some for admission or rejection, and move on. While their decision isn’t always final, in many cases theirs are the last eyes to look at the application itself.

The entire process can take less than eight minutes.

____________________________________

HOT TIP: HOW TO STAND OUT IN 8 MINUTES

Admissions officials and high-school counselors

give tips on getting a close look during quick application reviews:

Do:

• Keep essays focused and personal

• Highlight extracurricular activities that really mattered to you

• Tell a coherent story across essays, transcript and activities

Don’t:

• Use acronyms that only people familiar with your school would understand

• Assume the reader knows nothing about where you grew up

____________________________________

The new approach puts students at a disadvantage because an admission officer doesn’t get a comprehensive view of the candidate, some high-school guidance counselors say.

“If they’re splitting it up, it’s not holistic. Nobody has a full feeling” of the applicant, said Chris Reeves, a school counselor at Beechwood High School in Fort Mitchell, Ky., and a director at the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

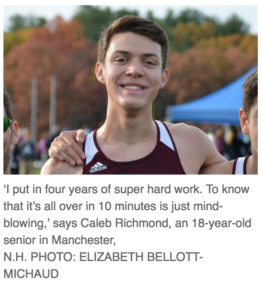

“I put in four years of super hard work. To know that it’s all over in 10 minutes is just mind-blowing,” said Caleb Richmond, an 18-year-old senior at the Derryfield School in Manchester, N.H., who says he wrote about seven drafts of his main college admission essay.

Committee-based evaluation, which involves a committee of two people, is the admission industry’s answer to ballooning application volume. Admissions directors say it is better for staffers than spending solitary months reading essays, transcripts and recommendation letters. They also say it helps train new readers and minimizes bias by forcing readers to defend why they think a candidate is qualified or not, and as a result they’re more confident in the decisions the new committees are making.

Admissions officers estimate that upward of 30 elite schools have embraced the method, championed early by the University of Pennsylvania. Colorado College, Case Western Reserve University, Swarthmore College and the California Institute of Technology use variations as well.

Schools say they are making the shift in part to stem staff turnover, as many now quit at the end of the reading season. “It’s a more humane way of reviewing applications,” said Marylyn Scott, senior associate dean of admissions at Bucknell. The school adopted the approach during the last admission cycle.

Readers at Bucknell, which gets more than 10,000 applications, used to take 12 to 15 minutes to review each application. Now a team of two is done in six to eight minutes.

Combined, Ms. Scott noted, that is still up to 16 “person minutes.”

Last year, the school admitted about 3,200 students and enrolled just shy of 1,000.

A three-person committee reviews the team’s notes before making a final call.

Efficiency is crucial, since more students are using the Common Application, which allows them to submit material to multiple schools. Nearly 902,000 students used it last year. As of Jan. 15 this year, the number was already 898,000 students submitting to an average of 4.8 schools.

Applications to Georgia Tech jumped by 13% for the coming academic year, to 35,600. The current freshman class has roughly 2,800 students.

“There’s just no way we could have gotten things done” without significant strain, said Rick Clark, director of undergraduate admissions.

That school introduced committee-based reading in the fall, and the staff, in up to 12 teams of two, now plows through about 500 applications a day.

The officer in charge of a particular region, referred to as the driver in the process, opens a file online and describes the applicant’s school to his or her partner, the passenger. The driver looks over an applicant’s academic transcript and test scores, while the passenger takes on counselor recommendations, essays and extracurricular activities.

They make a decision after eight to 10 minutes: admit, deny, waitlist. In about 85% of the cases, the application isn’t reviewed again.

“I’ve legitimately read—not skimmed, but read—more counselor recommendations in the last round than I have in the last three years,” Mr. Clark said. “I have time to read them.”

Critics say a fragmented reading provides little insight into candidates’ nuanced applications, and rather than reducing bias the team-based process can lead readers to reinforce one another’s assumptions.

Jim Conroy, chairman of the post high school counseling department at New Trier High School in Winnetka, Ill., says he spends years teaching colleges’ territory managers about his high school. Now, though, “There’s no context to their reading.”

Colleges say the committee would likely include the regional representative who knows about a school’s academic rigor and extracurricular offerings.

Still, some schools want to do things even faster.

Yvonne Romero da Silva, formerly at Penn and now vice president for enrollment at Rice, is focused on shaving a few more seconds off the process by reducing the number of text boxes into which readers can add notes and streamlining drop-down menus.

“Little things like that, after 40 files, really add up into concrete minutes,” she said, adding that the main goal is to spend that time on reading more closely.

Mr. Richmond, the senior from New Hampshire, agonized over his essay, about coming to terms with being gay.

“I can’t even tell you how many hours I stared at the page, just thinking about word choice, what I wanted the sentence to sound like,” said Mr. Richmond, who was accepted early to Swarthmore.

Then again, he said, “The process worked for me.”

Corrections & Amplifications

A photo above shows Mary Tipton Woolley and Xan Roseberry in the admissions office at Georgia Tech. An earlier version of the caption incorrectly gave their names as Mary-Tipton Woolley and Xan Rosenberry, and it incorrectly said the office is in the Georgia Tech Admissions Building. Separately, an earlier version of another photo caption incorrectly gave Rick Clark’s first name as Rich. (Jan. 31)

Appeared in the February 1, 2018, print edition as ‘Top Colleges Speed Read Applications How To Stand Out In Eight Minutes.’

…

rior to launching College Match in 2001, David worked with noted admissions expert Loren Pope. David has recently discussed an open mindset for college admissions as a panelist with Open Mindset author and Stanford University Professor Carol Dweck.

rior to launching College Match in 2001, David worked with noted admissions expert Loren Pope. David has recently discussed an open mindset for college admissions as a panelist with Open Mindset author and Stanford University Professor Carol Dweck.